In 2025, India wrapped up its third major trade agreement of the year, the India New Zealand Free Trade Agreement. This followed closely on the heels of the India UK trade deal and the India Oman partnership earlier, the same year. Clearly, the government has been in deal-making mode, pushing India deeper into global trade conversations.

But what caught our attention at Alphastreet’s research desk wasn’t India’s enthusiasm, it was New Zealand’s disappointment.

A day after the agreement was signed, New Zealand’s foreign minister publicly criticized the deal, calling it one sided. His biggest complaint? India had refused to open up its dairy sector. For a country that prides itself on dairy exports, this was seen as a missed opportunity.

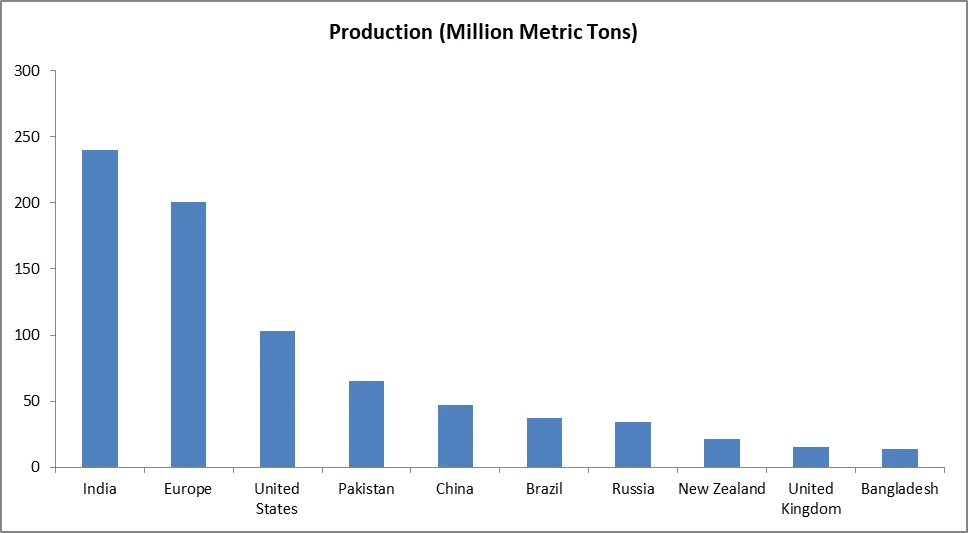

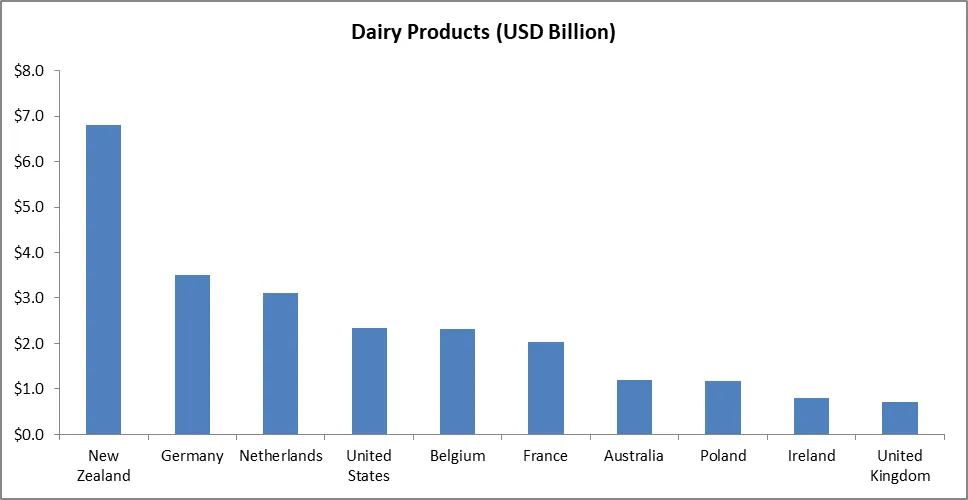

At first glance, India’s stance feels odd. After all, India is the world’s largest producer of milk. Yet when you look at global trade data, India barely features among dairy exporters. New Zealand ships out roughly $7 billion worth of dairy products each year. India manages about $400 million.

So why does the world’s biggest milk producer barely sell milk to the world?

Indians Drink What They Produce

The most obvious explanation is also the simplest. Indians consume an enormous amount of milk.

Unlike New Zealand or parts of Europe, where dairy farming is designed primarily for exports, milk in India is a staple of everyday life. From morning tea to curd, paneer, sweets, and religious rituals, milk is deeply embedded in daily consumption. Almost everything India produces is absorbed domestically.

But this explanation only goes so far. Even with high domestic demand, one would expect a country with India’s scale to export something at the margin. That it doesn’t points to deeper structural issues.

Dairy Is Daily Income, Not Just a Business

Nearly 90% of India’s milk comes from smallholder farmers, households that typically own five or fewer animals. Many of them also grow crops. For these families, milk isn’t a high margin commercial product. It’s daily cash flow.

Selling milk every day provides steady income and acts as insurance when crops fail. Dairy, in this context, is a risk management tool, not a profit maximising venture.

This structure creates a massive logistical challenge. Milk must be collected in tiny quantities from millions of scattered producers. Doing so requires an extensive network of village collection centres, transport routes, chilling facilities, and testing infrastructure.

And this is where cooperatives enter the picture.

What Dairy Cooperatives Actually Do

Almost every Indian state has its own dairy cooperative federation so for example, Amul in Gujarat, Verka in Punjab, Nandini in Karnataka, Aavin in Tamil Nadu, and Mahanand in Maharashtra, to name a few.

These cooperatives don’t “produce” milk. They aggregate it.

Their real achievement lies in building systems that reliably collect milk from millions of small farmers, test basic quality, and guarantee purchase at predictable prices. In doing so, they solve multiple problems at once, reducing dependence on middlemen, smoothing seasonal volatility by converting surplus milk into powder or butter, and ensuring profits flow back to farmers instead of outside shareholders.

On paper, cooperatives are farmer owned entities registered under state laws. In practice, many operate in close alignment with state governments. Management appointments, pricing decisions, expansion plans, and even branding often reflect political priorities.

This puts cooperatives in a grey zone, neither fully market driven nor fully state run.

Milk, Politics, and Price Control

Milk in India is classified as an “essential commodity” under the Essential Commodities Act. This gives governments wide powers to regulate pricing and distribution, especially during shortages.

In a normal market, rising demand would lead to higher prices, encouraging producers to supply more. In India, electoral considerations often override this logic. Governments are reluctant to raise consumer milk prices, particularly before elections.

When prices are capped, shortages don’t disappear, they just shift. Better-off consumers pay more in informal markets, while poorer households face reduced availability. Farmers, meanwhile, see their costs rise without the ability to charge more.

The absence of visible shortages shouldn’t be mistaken for a healthy system. Stress exists, it’s just absorbed quietly by producers.

Private players that offer higher procurement prices are often portrayed as disruptive or exploitative. But from an economic standpoint, preventing farmers from benefiting from higher demand only suppresses incentives to improve productivity.

Why Cooperatives Don’t Compete

Dairy cooperatives aren’t legally barred from competing with one another. But they were designed to operate within defined territories, often aligned with state borders, to ensure price stability.

Over time, this territorial logic hardened into political convention. State governments discourage cross-border competition because cooperatives are tools of food price management. Allowing competition risks losing control over both procurement prices and consumer prices.

The result isn’t a legal monopoly, but a politically enforced one.

Occasional attempts to break this pattern, such as Amul entering Karnataka or Nandini entering Delhi have triggered political pushback. Even when allowed, such expansions happen cautiously.

This lack of competition rewards stability, not innovation. Cooperatives become excellent at managing volumes and volatility, but weak at driving efficiency, productivity, or global competitiveness.

Can Private Players Change the Game?

The rise of private dairy companies like Hatsun, Heritage, and Country Delight is often seen as a sign of transformation. But these firms operate within the same fragmented production base as cooperatives.

They source from the same small farmers, face the same disease risks, and navigate the same pricing sensitivities. Their innovation lies mainly in branding, logistics, and consumer experience, not in fundamentally changing how milk is produced.

Country Delight, for instance, caters to premium urban customers willing to pay for traceability. Hatsun has built efficient regional brands. These are meaningful improvements, but they don’t resolve the core structural constraints.

Still, competition at the margins matters. It nudges cooperatives toward product innovation high-protein milk, value added dairy, and better packaging. Over time, this could lead to more genuine price discovery.

What Would It Take to Export Dairy?

India’s challenge isn’t cattle numbers but it’s productivity. Milk yield per animal remains low.

Cooperatives, with their long-term farmer relationships, are uniquely positioned to change this. But doing so would require redefining their role. Instead of absorbing all production, they would need to incentivize better outcomes, fewer animals, higher yields, improved feed, and better herd management.

Quality is the next barrier. Pooling milk works domestically, where standards are forgiving. Export markets demand traceability, consistency, and strict compliance standards that require farm level segregation and monitoring.

Then comes disease control. High-income markets have zero tolerance for endemic diseases and residue contamination. Until these issues are addressed systematically, Indian dairy remains locked out.

Cost is the final hurdle. Export competitiveness requires dedicated processing lines, long-term farmer contracts, and feed optimisation, all of which demand a more corporate operating model.

Rather than transforming the entire sector overnight, cooperatives could start with specific regions or clusters, applying strict standards and export oriented practices there. India has done this successfully in horticulture. Dairy could follow if politics allows differentiation.

The Real Constraint Is Political

Export orientation requires loosening state control over cooperatives and allowing market signals to operate more freely. That’s a political choice.

Until then, cooperatives will continue prioritising livelihood stability over global competitiveness not because they are inefficient, but because that is precisely what they were designed to do.

Addendum: When Firms Lead Instead of Cooperatives

India already has examples of what’s possible under a different institutional structure.

Producer companies like Sahyadri Farms operate outside the logic of price stabilisation and essential commodity politics. By organising farmers into tightly managed clusters and treating export markets as the end goal from day one, they enforce discipline.

Quality standards are strict. Poor produce is rejected, not absorbed. Disease control is non-negotiable. Pricing reflects market signals, not political convenience.

This model doesn’t eliminate risk, but it proves something important: Indian farmers can meet global standards when institutions are built for competitiveness rather than containment.

And that’s the real lesson behind why India doesn’t export milk which is not a lack of production, but a system optimized for stability, not scale on the global stage.