When India’s food delivery and grocery apps first took off, they seemed destined to reshape urban consumption. Venture capital flowed in, adoption surged, and companies like Zomato and Swiggy promised not just convenience but also enormous profitability once scale was achieved. A decade later, the story looks far less glamorous.

The problems aren’t new. In fact, the warning signs were visible as early as the ride hailing boom. Uber thrived in the US because car owners could drive part time, adding supply without major new costs. In India, however, driving a cab is still seen as a full time job. Uber and Ola drivers bought or leased vehicles, their income expectations matched traditional taxi drivers, and profitability only worked so long as deep discounts lasted. As fares normalized, margins collapsed and customer loyalty vanished.

Food and grocery delivery has followed a similar arc. Despite strong user numbers and steady revenue growth, the sector faces structural constraints: thin restaurant margins, capped household spending, gig worker under compensation, and intensifying competition. The numbers make the case clearer.

The Promise vs. Reality of Food Delivery

At its core, the aggregator pitch to restaurants was compelling: reach more customers through discovery, and grow sales by tapping into demand beyond dine-in. In theory, this should have expanded the pie. In practice, India’s restaurant industry has grown at roughly 9–11% annually, including inflation, showing little incremental boost from delivery.

Same store sales data tells the story. Specialty Restaurants grew per-store sales at just 2.5% annually over the past decade, below inflation. Devyani Foods, India’s largest chain operator, has even seen per-store sales decline since 2020. What delivery apps did achieve was a shift in consumption: dine in revenues got split with home delivery, which now carries a hefty commission.

Zomato’s take rate is around 30% on net order value, plus a 3% platform fee. Restaurants, already operating at sub 20% EBITDA margins, cannot absorb this without raising prices or cutting corners. Yet customers resist paying restaurant rates for food delivered at home, where the ambience and dining experience are missing. The result: cloud kitchens emerged as lower cost alternatives, and ONDC has undercut commissions to single digits.

Zomato today reports 23 million monthly active customers and 313,000 active restaurants. That looks impressive, but it essentially represents the urban ceiling: around 25–30 million households in India are realistically in the food delivery market, and Zomato already covers most of them. Swiggy, cloud kitchens, and ONDC overlap with the same base.

Meanwhile, customer behavior hasn’t changed much. The average customer spends Rs 1,567 a month on food orders, up just 21% in three years and about 6% annually, in line with inflation. Order frequency has not meaningfully increased. Growth, in other words, has plateaued.

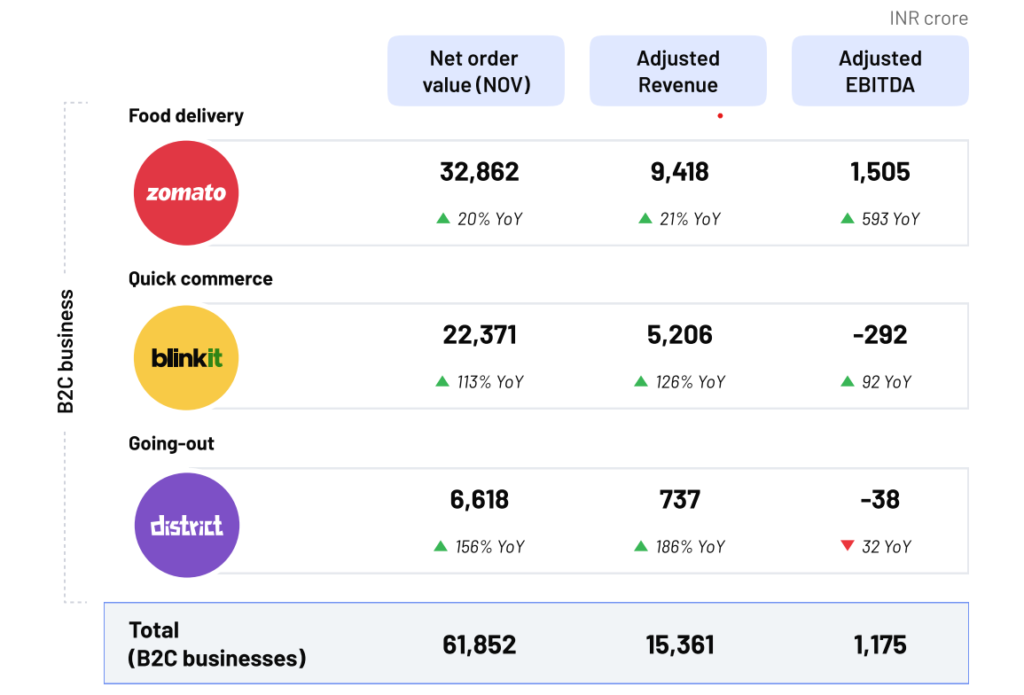

The Numbers Behind the Hype

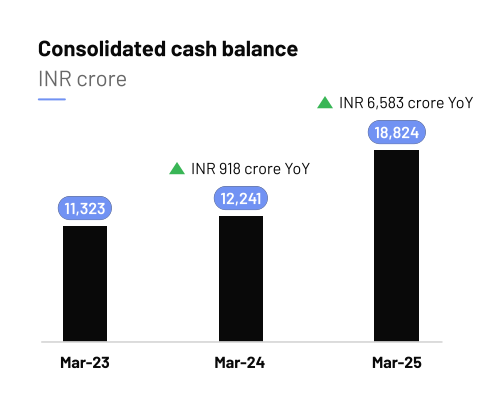

The financials reveal the underlying fragility of the model. Zomato may report headline profits, but they are almost entirely dependent on treasury income from its Rs 18,800 crore cash pile. In FY24–25, Zomato posted a net profit of Rs 351 crore. But treasury income alone was Rs 776 crore, and Rs 61 crore of tax liability was deferred. Strip those out, and the operating business was loss making.

The trend is worsening. In Q1 FY24–25, net profit was Rs 253 crore, with treasury income of Rs 255 crore meaning the core business actually lost money. By Q1 FY25 26, net profit had fallen to just Rs 25 crore, while treasury income rose to Rs 235 crore. Without treasury returns, Zomato’s operating losses have widened each quarter.

Advertising and promotions tell a similar story. Far from tapering off as adoption stabilizes, spending has increased, from Rs 396 crore in Q1 FY24–25 to Rs 671 crore a year later. This suggests that even at scale, Zomato is fighting hard just to retain customers.

For restaurants, the economics are underwhelming. The average Zomato partnered restaurant gets Rs 25,500 per month in orders, barely two orders per day at an average ticket size of Rs 408. Many could execute these orders themselves with existing staff, bypassing commissions altogether.

Delivery partners fare no better. Zomato’s 509,000 riders complete just 5.7 orders per day on average. Even at Rs 50 per delivery, that translates to less than the statutory minimum wage in most cities. Rider discontent is a persistent risk, with even minor strikes potentially driving mass customer migration to alternatives.

| Particulars (in Rs Cr) | Q1 24-25 | Q2 24-25 | Q3 24-25 | Q4 24-25 | Q1 25-26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net profit | 253 | 176 | 59 | 39 | 25 |

| Treasury income | 255 | 227 | 143 | 195 | 235 |

| Profit w/o treasury income | -2 | -51 | -84 | -156 | -210 |

| Particulars (in Rs Cr) | FY 22-23 | Q1 25-26 |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly revenue (gross* value) | 2192 Cr | 3590 Cr |

| Avg monthly revenue (fees) | 512.5 Cr | 885 Cr |

| Avg monthly customers | 17 Million | 22.9 Million |

| Gross value per customer in a month | Rs 1289 | Rs 1567 |

| Avg no. of restaurants | 2,10,000 | 3,13,000 |

| Avg no. of delivery partners | 3,26,000 | 5,09,000 |

| Gross order per restaurant in a month | 1.04 Lacs | 1.15 Lacs |

| Commission % (on gross) | 23.3% | 24.6% |

| EBIDTA % | 0 | 4.2% |

| Commission on net value | 29.6% | |

| Orders per rider in a day | 6.61 | 5.7 |

| Discounts | 20% | |

| Platform fee % | 3% | |

| Payment to riders (excl tips) | 3.8% |

The Grocery Gamble: Blinkit and Beyond

If food delivery looks capped, grocery “quick commerce” promised a new growth engine. Blinkit (Zomato), Instamart (Swiggy), and Zepto all pursued the dark-store model, betting that dense urban catchments would drive efficiency.

The scale has grown: Blinkit now covers 1,544 stores across 1,789 commercially viable PIN codes. Orders surged from 39 million in Q4 FY22–23 to 177 million in Q1 FY25–26, and active monthly customers rose from 3.9 million to 16.9 million in the same period. Yet profitability remains elusive.

Average order values hover at Rs 521, barely above the threshold for free gift promotions. Despite supermarket level gross margins (~21%), Blinkit still posts negative contribution margins per order: -1.8% EBITDA as of Q1 FY25–26. Orders per rider have actually fallen as volumes increased, undermining the scale efficiency thesis.

And competition is brutal. Zepto’s FY22 losses exceeded its revenue. Swiggy’s Instamart losses are expected to be even higher than Blinkit’s. Offline retailers like Reliance (JioMart), Tata (BigBasket), and Amazon Fresh are also entrenched in the same catchments. Price, not loyalty, drives most customer behavior.

| Q4 22-23 | Q1 24-25 | Q1 25-26 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 39.2 Million | 78.8 Million | 176.7 Million |

| Avg Net order value | Rs 522 | Rs 516 | Rs 521 |

| Avg monthly customers | 3.9 Million | 7.6 Million | 16.9 Million |

| Avg monthly riders | 1,05,000 | 2,43,000 | |

| Stores | 363 | 639 | 1544 |

| Discount (Gross-net value) | 16.8% | 16.8% | 20.0% |

| Revenue per Gross order value | 16.42% | 19.1% | 20.3% |

| Net order value per store in a day | 6.25 Lacs | 7.89 Lacs | 7.34 Lacs |

| EBIDTA as % Net Order Value | -9.9 | -0.1 | -1.8 |

| Orders per rider in a day | 10 | 10 | 9.7 |

Competition and Regulation

If economics weren’t enough, the external environment adds further headwinds.

- ONDC charges sub-10% commissions, directly challenging Zomato’s 30% model. In Bangalore, ONDC already accounts for 20% of delivery orders.

- Cloud kitchens like Rebel Foods, Curefoods, and Box8 bypass aggregators by owning both the kitchen and delivery, retaining margins. Yet even they remain unprofitable at scale.

- Gig worker legislation is looming, with potential increases to minimum wages. Given current rider pay is already at subsistence levels, even a 2% cost hike could wipe out Zomato’s margins.

- Tax and compliance risks persist, with a GST demand of Rs 803 crore. greater than Zomato’s cumulative profits to date. Dark stores in residential areas and lax FSSAI enforcement add to regulatory uncertainty.

The Outlook: Plateauing Growth, Structural Limits

The hard truth is that food and grocery delivery in India is no longer a growth story but it is a fight for survival in a saturated market. Zomato, Swiggy, Blinkit, Instamart, and Zepto already cover the commercially viable geographies and the bulk of the consuming class. Customers are spending more or less the same in real terms, while order frequency remains stagnant.

On the supply side, restaurants resist high commissions, riders earn below minimum wage, and cloud kitchens add to competition. On the demand side, customers are highly price-sensitive, switching platforms based on discounts and offers.

For investors, the message is sobering. Zomato’s reported profitability is sustained by treasury income, not operating leverage. Blinkit’s scale has not delivered efficiencies, and competition only intensifies. With ONDC and regulatory risks pressing down, the upside narrative is weak.

The aggregator model has solved genuine customer pain points: discovery, convenience, and reliability. But the Indian market size is limited, the economics are fragile, and margins are capped. Fifteen years in, the industry has plateaued. What remains is not the story of exponential growth, but of consolidation, cost pressures, and a long struggle for sustainable profitability.