Every electric vehicle boom tends to have a flagship success story. In the US, Tesla played that role, burning cash for years before scale finally unlocked profitability. In China, BYD followed a different path, patiently building batteries, owning its supply chain, and waiting for the right mix of policy support and demand.

In India, many believed that role belonged to Ola Electric. But whether it truly does is now an open question.

Ola was one of the rare Indian startups willing to take the manufacturing plunge instead of staying comfortable as an assembler or importer. While others took cautious steps, Ola tried to compress an entire EV journey into a short span, setting up a massive factory in Tamil Nadu, aggressively localizing components, and focusing squarely on two-wheelers, the segment that actually defines Indian mobility. That decision gave the company instant scale and visibility.

At the same time, Ola understood branding better than most incumbents. It sold electric scooters not just as vehicles, but as consumer tech, sleek design, connected features, and sharp pricing wrapped in high-energy launches. Combined with a D2C sales model, this helped Ola capture attention far faster than legacy manufacturers that were still experimenting cautiously.

In doing so, Ola behaved exactly like a startup should: move fast, disrupt norms, and force an entire industry to accelerate.

When Ambition Meets Reality Ft OLA

In spirit, Ola’s playbook resembled Tesla’s and BYD’s. But history shows that the hardest phase for these companies wasn’t when they were losing money early on. It was when demand surged and they had to prove that ambition could translate into operational discipline, consistent quality, and sustainable margins.

That is precisely the phase Ola Electric has now entered. And it’s why the recent sale of shares by founder Bhavish Aggarwal, along with mounting execution challenges, has drawn so much attention.

To understand why, it helps to step back.

From EV Poster Child to Pressure Point

Ola Electric was once seen as the face of India’s EV ambitions. Backed by SoftBank, it promised speed, scale, and vertical integration. It invested heavily in gigafactories, built batteries and software in-house, and ramped up scooter production rapidly. For a period, this translated into impressive revenue growth.

The numbers look strong at first glance. Revenues jumped from around ₹400 crore in FY22 to roughly ₹2,600 crore in FY23, and then to about ₹4,500 crore by FY25. Very few manufacturing startups manage to scale that quickly.

But losses expanded just as fast. Net losses grew from about ₹1,470 crore in FY23 to ₹2,200 crore in FY25, and have already crossed ₹2,280 crore this year. Growth came at a steep cost.

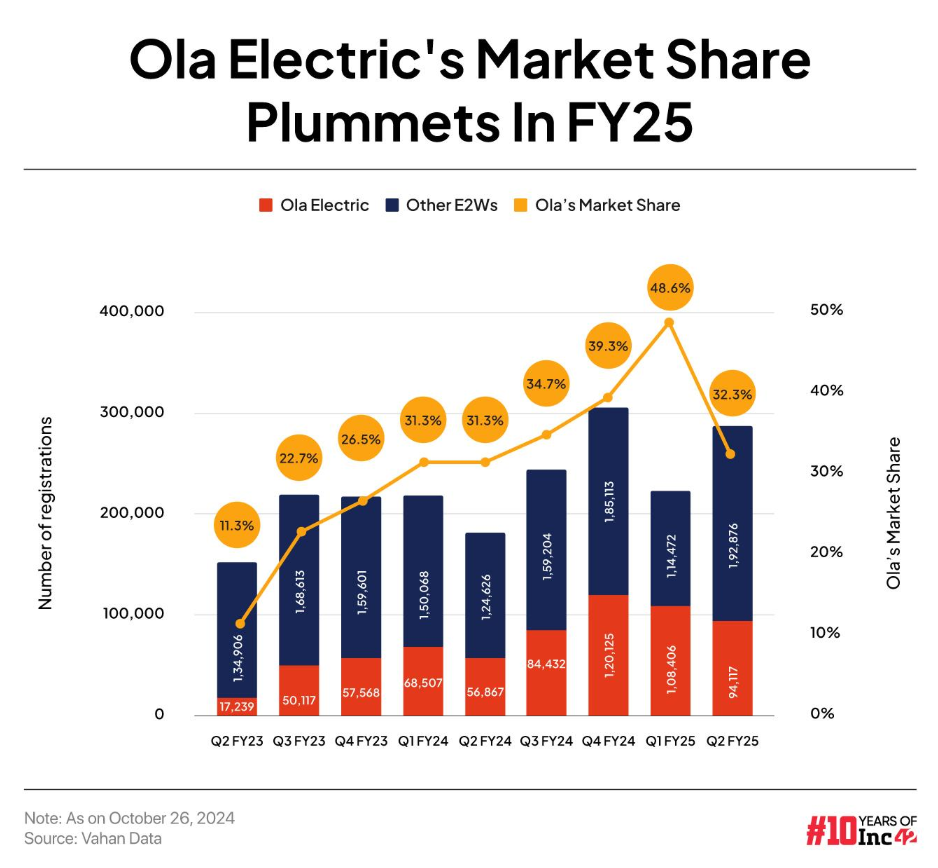

Since the IPO, the narrative has shifted further. Aggarwal has been gradually selling shares, operational issues have surfaced, and customer complaints have mounted. Meanwhile, competition from TVS, Bajaj, and Ather has only intensified.

A Tech Mindset in a Manufacturing World

At its core, Ola Electric is running a capital-intensive manufacturing business. It sells scooters on thin margins to capture market share, betting that scale, software services, financing, and eventually battery production will drive profitability later. This loss leader approach works well in tech platforms.

The problem is that Ola is not a tech company that happens to manufacture. It is a manufacturer trying to operate with tech like speed. While this is admirable in a country that needs more manufacturing ambition, it introduces serious risks.

Manufacturing doesn’t forgive mistakes the way software does. Bugs in an app can be patched. Defects in a factory reach customers. When that happens, costs explode simultaneously, warranty claims rise, service centres get overwhelmed, logistics expenses increase, and brand trust erodes faster than marketing can repair it.

Scaling Faster Than Systems

This strain also showed up in Ola’s retail expansion. In a short period, the company expanded its physical stores from around 800 to nearly 4,000. But regulatory filings later revealed that Ola lacked clear visibility into inventory levels across these outlets.

The consequences soon followed. Rapid scaling exposed weaknesses in quality control and after-sales service. Reports of breakdowns, battery failures, and long service delays became common. Each fix or replacement chipped away at margins that were already razor-thin.

Subsidies Fade, Pressure Builds

Ola’s growth phase was also helped by generous government subsidies under the FAME scheme. These incentives kept prices competitive and volumes high. But as subsidies were gradually reduced, the economics tightened.

When incentives shrink, companies face a choice: raise prices or absorb the hit to margins. In a fiercely competitive market, price hikes are risky, leaving profitability under pressure.

Legacy Players Strike Back

Early on, Ola and Ather had a clear advantage because incumbents like TVS and Bajaj were slow to move. That gap has now closed. Legacy manufacturers have caught up on product quality, battery reliability, and software features.

Bajaj Auto, in particular, stands out. Its EV segment is already EBITDA-positive, meaning it doesn’t lose more money as volumes increase. And legacy players bring something Ola is still buildingm dense, reliable service networks. For many customers, access to service matters more than apps or launch events.

Building that network from scratch is expensive, and the benefits take time to materialise.

The Double-Edged Sword of Vertical Integration

Ola’s bet on vertical integration gives it control, but it also front-loads costs. Factories, R&D, depreciation, and payroll expenses hit the income statement long before volumes can absorb them. The entire model depends on demand arriving quickly and staying strong. Any slowdown turns fixed costs into a heavy burden.

This context is critical when looking at Bhavish Aggarwal’s share sales.

Founders sell shares for many reasons: liquidity, diversification, or tax planning. On its own, that’s not alarming. What makes markets uneasy is the timing. Ola remains loss-making, cash burn is high, and there is no clear inflection point where losses start shrinking meaningfully. Even if the stated reason is loan repayment, reducing exposure at this stage raises questions about what lies ahead.

Alignment, Risk, and Market Perception

There’s also a personal finance angle. Ola Electric represents a large portion of Aggarwal’s net worth. Selling some stake converts paper wealth into liquid assets without relinquishing control. From an individual risk perspective, that’s sensible.

From a public market perspective, however, it weakens the alignment signal investors look for especially in capital-heavy businesses that require patience and long-term conviction.

Adding further uncertainty is Ola’s recent expansion into adjacent products like inverters and energy solutions. While this could improve factory utilisation, it also raises questions. Are these high-margin extensions, or temporary fixes to spread fixed costs more thinly? The answer will shape both margins and strategic focus.

The Hardest Phase of OLA’s Journey

What’s happening at Ola Electric isn’t a collapse. And it isn’t a scandal.

It’s something far more common and far more difficult. The company has entered the toughest phase of its lifecycle. The phase where vision must give way to execution discipline. Where scale has to start delivering profits, not just growth headlines.

Ola’s ambition pushed the Indian EV industry forward. But manufacturing is unforgiving, and public markets are far less patient than venture capital.

The next chapter for Ola Electric won’t be decided by how bold its plans sound, but by whether profits begin moving in the right direction. If they do, today’s share sales will fade into the background. If they don’t, they may come to be seen as an early warning.