Incorporated in 1987, Bal Pharma Limited is engaged in manufacturing, marketing and selling of pharmaceutical products. The company caters to both domestic and international markets.

Financial Results:

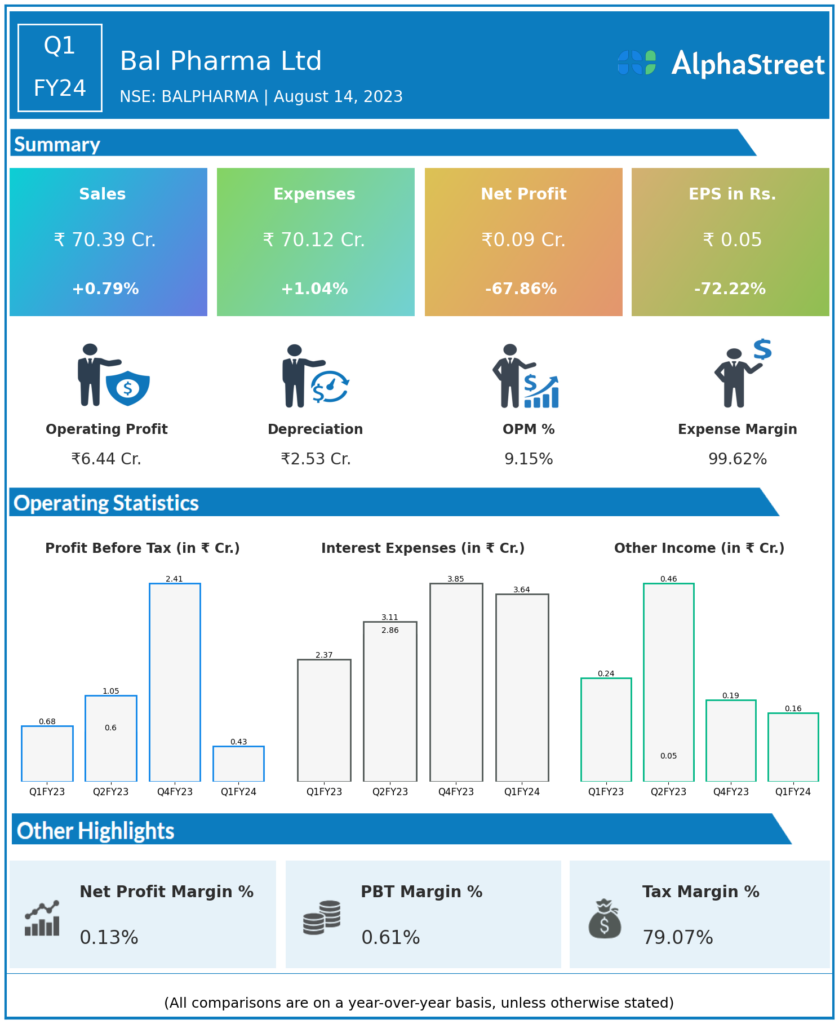

Bal Pharma Ltd reported Revenues for Q1FY24 of ₹70.39 Crores up from ₹69.84 Crore year on year, a rise of 0.79%.

Total Expenses for Q1FY24 of ₹70.12 Crores up from ₹69.40 Crores year on year, a rise of 1.04%.

Consolidated Net Profit of ₹0.09 Crores down 67.86% from ₹0.28 Crores in the same quarter of the previous year.

The Earnings per Share is ₹0.05, down 72.22% from ₹0.18 in the same quarter of the previous year.

*It is important to note that the way the results have been accounted for are slightly different than the ones the companies may choose to publish.

*The presented data is automatically generated. It may occasionally generate incorrect information.